This is a series of posts on the importance of data in policymaking. It focuses on the Indian context.

One of the most important tools for a Policymaker is reliable data. The lack of reliable current time data results in the paralysis of the most well thought about policies. All efforts to create great policy are futile in the absence of data. This was most evident during the mass exodus of Migrant workers towards their home states during the COVID pandemic last year. Devising effective policies and programmes targetting migrant workers was next to impossible. We had no idea about the number, we did not know what the demographic composition of the migrant workers was, How many were men vs women vs children, What was their home state distribution, What was their income levels? This also explains the ineffectiveness and inadequateness of all of the Goverment’’s efforts to benefit migrant workers. They launched the Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyan, a rural public works scheme to employ returning migrants in some states. They increased budget allocations to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). Special Shramik trains were organised to help migrant workers travel to their home towns. However, none of these efforts was half as effective as they were envisioned to be. The main reason being data insufficiency. The Government seems to have realised this and the Ministry of Labour has recently launched two national surveys—one to track migrants, their socio-economic conditions and shifting preference for jobs, and the other to gather primary job creation numbers from 150,000 companies. The last migration survey was conducted more than a decade ago. This clearly reflects the importance placed on data in our country. We have launched multiple schemes for migrants without having any evidentiary data for their potential success. The recent surveys launched by the Government will hopefully place us in a better place to be able to draft well-informed impact-focused policies and programmes. For a country that is aiming at being becoming a 5 trillion $ economy by 2025, our official data reliability is dismal.

We have massive debates on unemployment and job creation. Every news channel is a platform for cacophony on berozagaari, the opposition is crying itself hoarse on an all-time high unemployment rate and there are long opinion pieces on national dailies about lack of job creation. However, everyone seems to miss the main point. We have no reliable data on employment in our country. Everyone is playing on estimates, sensationalizing the lack of jobs and politicising job creation. Data Credibility and availability in our country is a major challenge.

The Central Government as a means to clear the air on data credibility of official data constituted the Standing Committee on Economic Statistics (SCES) headed by Ex-Chief Statistician Pronab Sen in December 2019. The SECS constituted three sub-committees: one for the Periodic Labour Force Survey and time use survey; second for IIP and Annual Survey of Industries (ASI); and the third for the Annual Survey of unincorporated sector enterprises and services sector data. This committee has been the forerunner to deliberate and develop methodologies for surveys on industry, services and employment in place of multiple panels on these issues. It is aimed at bringing the reliability factor to official statistics and data published by the Government.

Is constituting a committee enough to solve India’s data crisis? Certainly not. India has to re-work its entire data management system to ensure that it has a data-driven approach to policymaking and delivery of services. Looking at the evolution of India's approach to data will help understand India’s struggles with data gaps better. India pre-2019 had the following statistical framework.

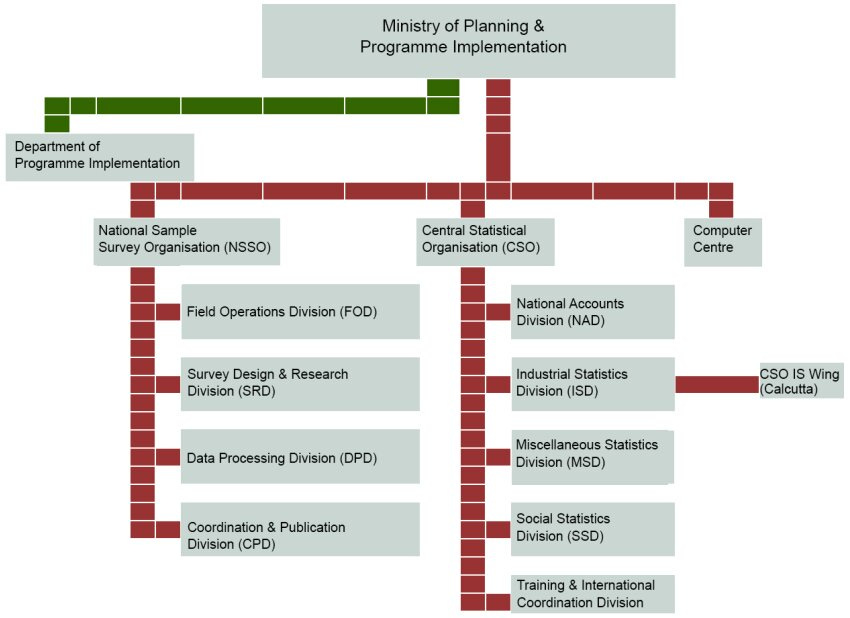

Under the Ministry of Planning &Programme Implementation, there were mainly two categories, one relating to Statistics and the other- Programme Implementation. The one related to statistics was called the National Statistical Office (NSO) consisting of the Central Statistical Office (CSO), the Computer Center and the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). The other category of Programme Implementation had three divisions, (i) Twenty Point Programme (ii) Infrastructure Monitoring and Project Monitoring and (iii) Member of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme. In addition to this, there was the National Statistical Commission created through a resolution of the Government of India (MOSPI) and the Indian Statistical Institute which made up the official statistical framework in India. The NSC had the mandate to evolve policy and technical standard for statistical practices.

In May 2019 the Ministry of Statistics and Programme implementation (Mospi) passed an order on 23 May to merge the Central Statistics Office (CSO) and National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) into the National Statistical Office (NSO). This merger was a suggestion made by a committee headed by C.Rangarajan in 2000. The Government stated that they did this to streamline and strengthen the nodal functions of the statistics ministry. The order essentially reduced the status of the NSC. It also stated that the proposed NSO would be headed by Secretary (Statistics and Programme Implementation). This order essentially centralized the statistical system in the country.

I find a couple of drawbacks to the new system. Firstly, this level of centralisation has essentially made the data generator and user the same. The other concern is that this merger which has led to centralisation will lead to a slower release of data into the public sphere. This is a grave concern. For example in scenarios where data is required immediately for public research or time-sensitive policy deliberation, lack of timely availability of data defeats the purpose of a statistical agency. Another pressing concern is the move towards centralisation in the name of administrative ease and accountability.

However, all this reshuffling and revamping the statistical system has not made India a data robust nation. Neither has it helped policymakers gain access to reliable data while framing policy.